Evaluating seminal works of architecture requires high professional competence and an ability to see the big picture.

Therefore, The OBEL AWARD appoints a jury that consists of members with a strong architectural profile but also distinguished professionals from other backgrounds.

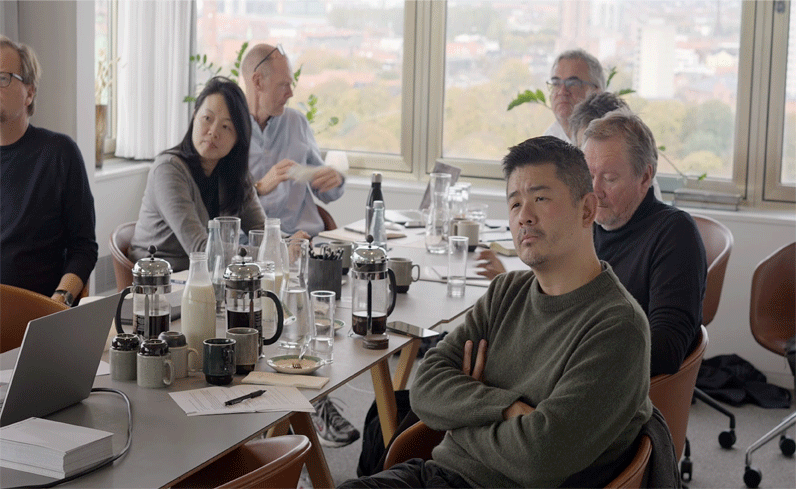

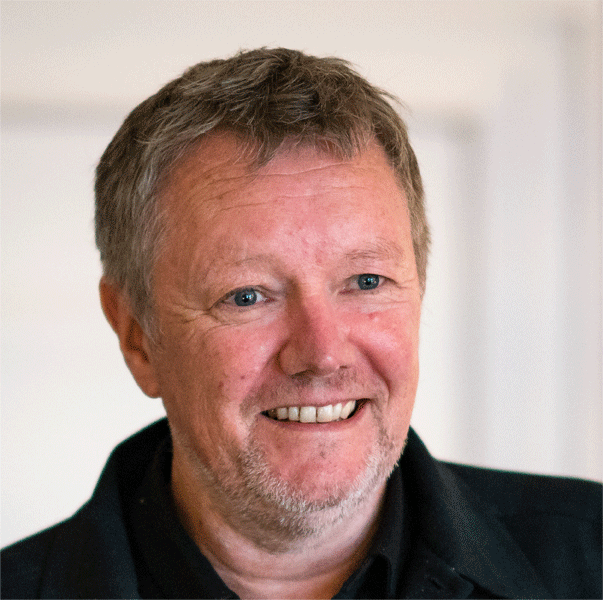

Kjetil Trædal Thorsen

Chair of Jury

Snøhetta

AIA, FRIBA

Kjetil Trædal Thorsen co-founded the renowned firm Snøhetta, established in 1987 in Oslo, Norway. He has been instrumental in defining Snøhetta’s philosophy and growth into a collaborative, transdisciplinary, and global practice that brings together architecture, landscape architecture, interior architecture, art, product design, and graphic and digital design in its offices throughout the world.

Kjetil Trædal Thorsen completed his architectural training in Graz, Austria. A year later, in 1986, he co-founded Norway’s first independent architectural gallery, Galleri ROM, specializing in experimental architecture, visionary architecture, and architecture which integrates socio-political approaches.

read more

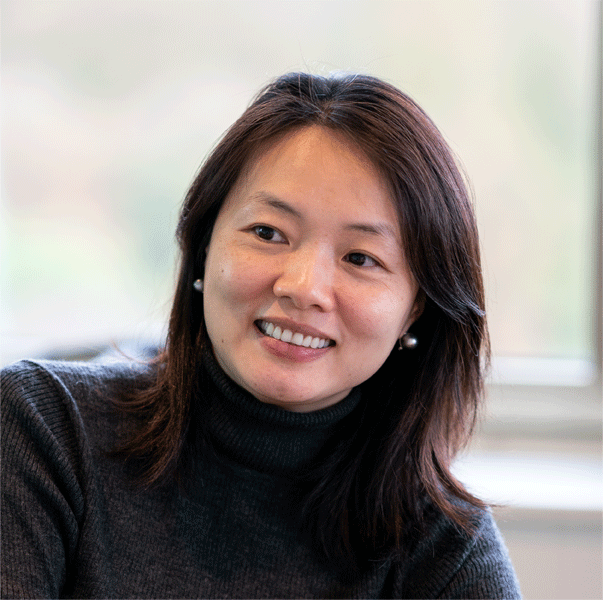

Xu Tiantian

DnA _Design and Architecture

Hon. FAIA

Xu Tiantian is founding principal of the DnA _Design and Architecture Beijing office, an interdisciplinary practice working with city planning, urban design, and architectural design with a special focus on addressing new relationships between architecture and urbanism in contemporary Chinese culture.

She has received numerous awards throughout her career and in 2020, she was appointed an Honorary Fellow of American Institute of Architects. Xu Tiantian holds a Master of Architecture in Urban Design from Harvard Graduate School of Design and Bachelor of Architecture from Tsinghua University in Beijing. She has taught at the Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA) School of Architecture in Beijing, China.

read more

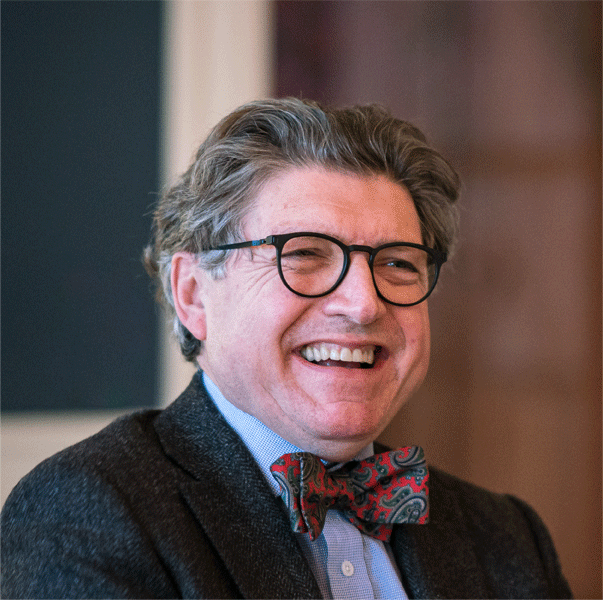

Wilhelm Vossenkuhl

Wilhelm Vossenkuhl

Prof. em. Dr.

Wilhelm Vossenkuhl is professor emeritus at the Ludwig-Maximilians-University in Munich. Much of Wilhelm Vossenkuhl’s work is focused on the relationship between architecture and philosophy. He has been involved in several design projects with, for example, Otl Aicher and Norman Foster. His current work focuses on the reform of design education undertaken in collaboration with university colleagues.

Wilhelm Vossenkuhl is the author and editor of numerous books and publications that include many contributions to ethics. He holds a Ph.D. in philosophy from Ludwig-Maximilians-University in Munich and post-doctoral research at Cambridge University. He has undertaken teaching at the University of Bayreuth, the Faculty of Design and Architecture at the Academy of Arts, Stuttgart, and the universities of Freiburg, Krakow, and Lodz, among others.

Nathalie de Vries

mvrdv

Hon. FAIA, International FRIBA, BNA

Nathalie de Vries (Appingedam, NL – 1965) is founding partner of MVRDV, an architect and urban planner and the “DV” in MVRDV. The work of De Vries focuses on the invention of new building typologies and the creation of changeable, open systems, an approach which she brings to both buildings and urban plans. As an architect, she appreciates intensive collaboration with clients and interdisciplinary design teams, but also with residents and other stakeholders. Whatever the project, there is always a lot of attention given to the design’s interaction with its surroundings, by designing inviting collective spaces and outdoor areas, among other approaches. In her urban designs, De Vries explores the combination of high-quality public spaces with functionally mixed buildings that act as catalysts for the development of an area. De Vries is committed to the education of future generations of architects. She has been active as a teacher throughout her career, and she is currently Professor of Architectural Design and Public Building at Delft University of Technology. Previously, she taught at TU Berlin, Harvard GSD, IIT Chicago, and the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, among others.

read more

Louis Becker

Henning Larsen Architects

MAA, Int. AIA, RIBA, Hon FRIAS

Louis Becker is Design Principal and Partner at Henning Larsen Architects. Becker has played an integral role in the internationalization of Henning Larsen, and he remains a driving force in the expansion of the global impact of the practice at the intersection between knowledge, professionalism, and artistic quality. Taking a context-driven approach to the design process, he tackles every project based on the conviction that architecture must speak directly to users and give back to the society in which it exists.

A guest lecturer at many universities and congresses, he is an Adjunct Professor at the Aalborg University Institute of Architecture, Design and Media Technology. He is also invited to serve on architectural competition juries.

Sumayya Vally

Counterspace

Founder and principal of the award-winning architecture and research studio Counterspace, Vally’s design, research, and pedagogical practice is searching for expression for hybrid identities and territory, particularly for African and Islamic conditions — both rooted and diasporic. The practice occupies a space between the functional and the speculative, pedagogy and praxis, simultaneously describing cities and their histories and futures and imagining them. Her design process is often forensic and draws on the aural, performance, and the overlooked as generative places.

Vally has always been involved in academics and has taught at The Bartlett, University of Sydney, Graduate School of Architecture, University of Johannesburg, and the University of Illinois, USA. In 2022, Vally was selected by the World Economic Forum to be one of its Young Global Leaders and, in 2021, was named TIME100’s Next list honoree. Vally completed her undergraduate studies in Architecture at the University of Pretoria and her master’s degree at the University of the Witwatersrand.

Aric Chen

Nieuwe Instituut of Netherlands

Aric Chen is General and Artistic Director of the Nieuwe Instituut, the Netherlands’ national museum and institute for architecture, design, and digital culture in Rotterdam. American-born, Chen previously served as Professor and founding Director of the Curatorial Lab at the College of Design & Innovation at Tongji University in Shanghai; Curatorial Director of the Design Miami fairs in Miami Beach and Basel; Creative Director of Beijing Design Week; and Lead Curator for Design and Architecture at M+, Hong Kong, where he oversaw the formation of that new museum’s design and architecture collection and program. Chen is the author of Brazil Modern (Monacelli, 2016), and has been a frequent contributor to The New York Times, Wallpaper, Architectural Record, and other publications.

read more